Posted by: Bob Williams

Imagine a Rochester without an noose-like expressway dividing downtown-adjacent neighborhoods on the north and east sides. An obstacle to true connectivity for over 50 years, imagine the loop and its ramps filled in to grade instantaneously at the snap of your fingers. Naturally the next question arrives in our minds immediately, ‘How will we utilize this reclaimed real estate?’

Imagine a Rochester without an noose-like expressway dividing downtown-adjacent neighborhoods on the north and east sides. An obstacle to true connectivity for over 50 years, imagine the loop and its ramps filled in to grade instantaneously at the snap of your fingers. Naturally the next question arrives in our minds immediately, ‘How will we utilize this reclaimed real estate?’

If the goals are to reconnect severed neighborhood conduits, promote commerce, reduce car dependence, ensure ease of navigation, and foster a dynamic and vibrant streetscape, the answer lies not in a grandiose vision of the future, but more likely in our historic roots.

If the goals are to reconnect severed neighborhood conduits, promote commerce, reduce car dependence, ensure ease of navigation, and foster a dynamic and vibrant streetscape, the answer lies not in a grandiose vision of the future, but more likely in our historic roots.

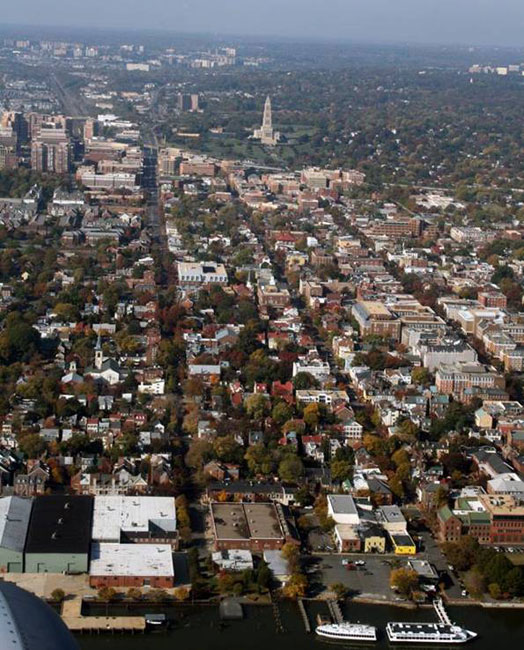

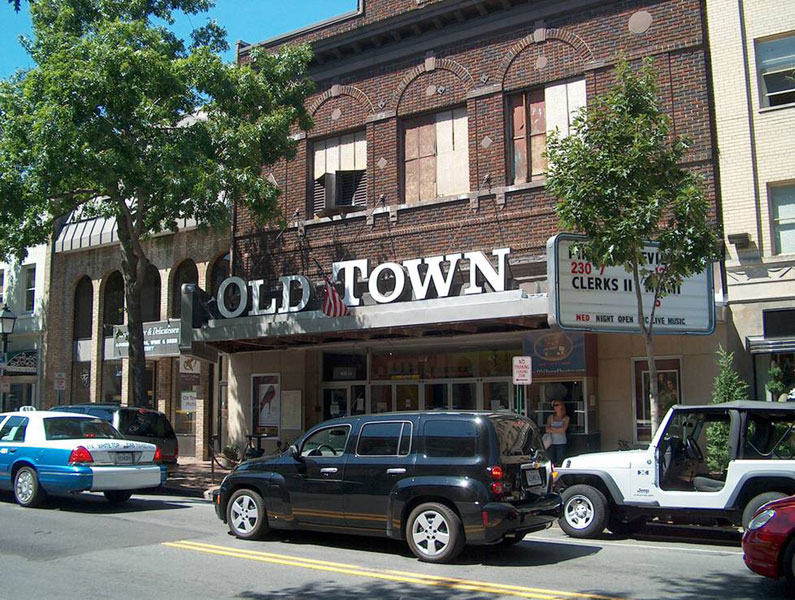

Consider the example of Alexandria, Virginia![]() . Originally platted in 1749 on land donated by Philip and John Alexander, six fundamental tenets of Traditional Neighborhood Development (TND) differentiate this inviting river city from generic drivable suburbanism…

. Originally platted in 1749 on land donated by Philip and John Alexander, six fundamental tenets of Traditional Neighborhood Development (TND) differentiate this inviting river city from generic drivable suburbanism…

Rule 1: The Center

Each neighborhood should have a clear center. The focus of this central meeting point should be on commercial, cultural, and governmental activity.

Rule 2: The Five Minute Walk

Residents of Alexandria are rarely more than a five minute walk from their daily needs, including retail and occupational sites, some of which are located at the same site.

Rule 3: The Street Network

Alexandria’s streets form a grid of small blocks which allow for numerous routes connecting one point to another. Traffic is more easily diffused by presenting the individual with added navigation options. As the streets travel parallel and perpendicular paths, ease of orientation is enhanced.

Rule 4: Narrow Versatile Streets

The narrower streets found in our older cities have a calming effect on traffic. This makes the sidewalk pleasant and safe to walk along. Further enhancements are made to a pedestrian-friendly environment by widening sidewalks, the presence of shade trees, and the outdoor room effect creating by buildings close to the street.

Rule 5: Mixed Use

Multiple uses for a building help to ensure a constant rotation of users of the street space as well as constant monitoring by occupants. Buildings should be arranged by their physical type, not by their use. Use-based segregation is the case in common restrictive zoning laws which would render a place like Alexandria illegal to replicate today.

Rule 6: Special Sites for Special Buildings

Traditional neighborhoods locate important structures such as schools, places of worship, and other civic buildings at prominent sites within the street grid. These larger structures, generally of higher architectural quality, serve to terminate vistas, in a pleasing as well as orienting manner, as residents and visitors travel along the corridors. Alexandria’s City Hall sits back from the streets on a plaza, one of few buildings in town to do so. This plaza takes on added importance on Sundays as it hosts an area farmer’s market.

Some Examples…

A fine example of TND carried out on a blank canvas is Memphis’ Harbor Town![]() . Envisioned as a pre-war, pre-automobile style neighborhood by Henry Turley, ground was broken in 1989 at a site just northwest of downtown Memphis on what was previously a sandbar in the Mississippi known as Mud Island. A design review process for each new house ensured a neighborhood fit and enhanced the building process. Commercial tenants in Harbor Town include a small grocery store, a gift/garden shop, a bilingual daycare, and a hotel.

. Envisioned as a pre-war, pre-automobile style neighborhood by Henry Turley, ground was broken in 1989 at a site just northwest of downtown Memphis on what was previously a sandbar in the Mississippi known as Mud Island. A design review process for each new house ensured a neighborhood fit and enhanced the building process. Commercial tenants in Harbor Town include a small grocery store, a gift/garden shop, a bilingual daycare, and a hotel.

A significant infill project in the TND idiom was undertaken in Safety Harbor, Florida![]() only a few years ago. The anchor, known as Harbor Pointe offers up 15,000 square feet of ground floor retail (Ice Cream, Wine, Cell Phone, and Coffee shops) with a 5,000 square foot restaurant tenant at the corner of Main Street and Bayshore Boulevard. Rule 5: Mixed use was certainly ascribed to as this development boasts 25,000 square feet of office space on the 2nd and 3rd floors and is the first stage of a development area that would add residential in the form of condominums.

only a few years ago. The anchor, known as Harbor Pointe offers up 15,000 square feet of ground floor retail (Ice Cream, Wine, Cell Phone, and Coffee shops) with a 5,000 square foot restaurant tenant at the corner of Main Street and Bayshore Boulevard. Rule 5: Mixed use was certainly ascribed to as this development boasts 25,000 square feet of office space on the 2nd and 3rd floors and is the first stage of a development area that would add residential in the form of condominums.

With an eye toward sustainability, reuse and restoration are an important part of neighborhood development. In 2003, Ken Marquis of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania bought the Casey Laundry building in nearby Scranton![]() . Constructed in the 1920’s, the building originally served as an ancillary services annex for the since demolished Hotel Casey complex. The refurbishment created three large apartments, one on each of the upper floors of the building. The 1st and 2nd floors host a loft-style art and frame store as well as a small coffeehouse.

. Constructed in the 1920’s, the building originally served as an ancillary services annex for the since demolished Hotel Casey complex. The refurbishment created three large apartments, one on each of the upper floors of the building. The 1st and 2nd floors host a loft-style art and frame store as well as a small coffeehouse.

Traditional Neighborhood Design has shown itself to be up to the challenge of some of the most seemingly intractable neighborhood improvement issues. Let us return to our Inner Loop example. Imagine we are told that the expressway will never be removed. This was the scenario presented to the residents of Columbus, Ohio’s Short North neighborhood![]() . The routing of Interstate 670 isolated this neighborhood from the rest of the city, leading to the type of crime and abandonment issues seen across the country in neighborhoods destroyed by freeway construction. The solution to the lack of connectivity was the I-670 ‘Cap.’ The cap actually consists of two additional bridges erected on either side of the overpass. Each bridge is host to buildings that front on High Street, in much the same way that Rochester’s Main Street Bridge used to function. As a result of this pioneering design, pedestrians and diners at sidewalk cafes don’t even realize they are on a bridge over an interstate. Now connected to the convention center district at the north end of downtown, the Short North has seen spillover development in the form of 160 new housing units on a 3.2 acre site called Victorian Gate.

. The routing of Interstate 670 isolated this neighborhood from the rest of the city, leading to the type of crime and abandonment issues seen across the country in neighborhoods destroyed by freeway construction. The solution to the lack of connectivity was the I-670 ‘Cap.’ The cap actually consists of two additional bridges erected on either side of the overpass. Each bridge is host to buildings that front on High Street, in much the same way that Rochester’s Main Street Bridge used to function. As a result of this pioneering design, pedestrians and diners at sidewalk cafes don’t even realize they are on a bridge over an interstate. Now connected to the convention center district at the north end of downtown, the Short North has seen spillover development in the form of 160 new housing units on a 3.2 acre site called Victorian Gate.

We Can Be Change Agents…

In closing, obstacles to the common sense approach that is TND still exist in the form of single use zoning, financial policy, traffic engineers, perceptions of open space, income segregation, the development industry, taxation schemes, permitting processes, and the diminished role of architects. What we as citizens can do is play the role of the generalist, one whose focus is not narrowly limited to one issue such as traffic, housing, schools, crime, or the environment. These issues are largely interrelated and can be successfully addressed if taken together in the context of the neighborhood. The generalist’s role in advancing this approach is to champion change in local governmental policy by demanding that:

- Community Design be put back on the agenda. In order to be effective, policy that impacts the physical environment must be preceded and justified by a specific physical vision.

- Regulations be rewritten. Do not try to fix old zoning codes, the best way to upgrade a development code is to start from scratch to avoid creating an even more confusing code.

- Government be proactive. The local planning department must be empowered and encouraged to propose development patterns ahead of the private sector.

- Planning be regional in nature. Local municipalities must act with the understanding that the most meaningful planning occurs at the regional scale.

- Public participation is encouraged and ideas implemented. Citizen participation in the planning process has proved to be the most effective way to avoid mistakes.

- Future government buildings follow these guidelines. Location and design of municipal buildings sets an important example.

For more on Traditional Neighborhood Design, see the following reference material:

Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream

Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Jeff Speck

New York : North Point Press, 2000

Central Library: 307.7609 D812s

Home from Nowhere: Remaking our Everyday World for the Twenty-first Century

James Howard Kunstler

New York : Simon & Schuster, 1996

Central Library: 307.12 K96h

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Jane Jacobs

New York : Random House, 1961

Central Library: 711 J17d

Coincidentally, today in an all day openhouse Buffalo unveils their new zoning code, http://BuffaloGreenCode.com.